The Magic Realism of Dudley Huppler & Jean Jones Jackson

February - March 2023

Side Room is pleased to present its next exhibition, The Magic Realism of Dudley Huppler & Jean Jones Jackson, a dual-person show that brings together the idiosyncratic drawings and paintings of these two historical contemporaries and friends. This exhibition, which will be on view online through February 28, 2023, includes three drawings by Dudley Huppler (1917-1988) and two paintings and one drawing by Jean Jones Jackson (1907-1984), all made in the decade between 1953 and 1964. This is the first exhibition to pair the work of these two kindred spirits, whose liminal place in Post-War American Art begs further examination.

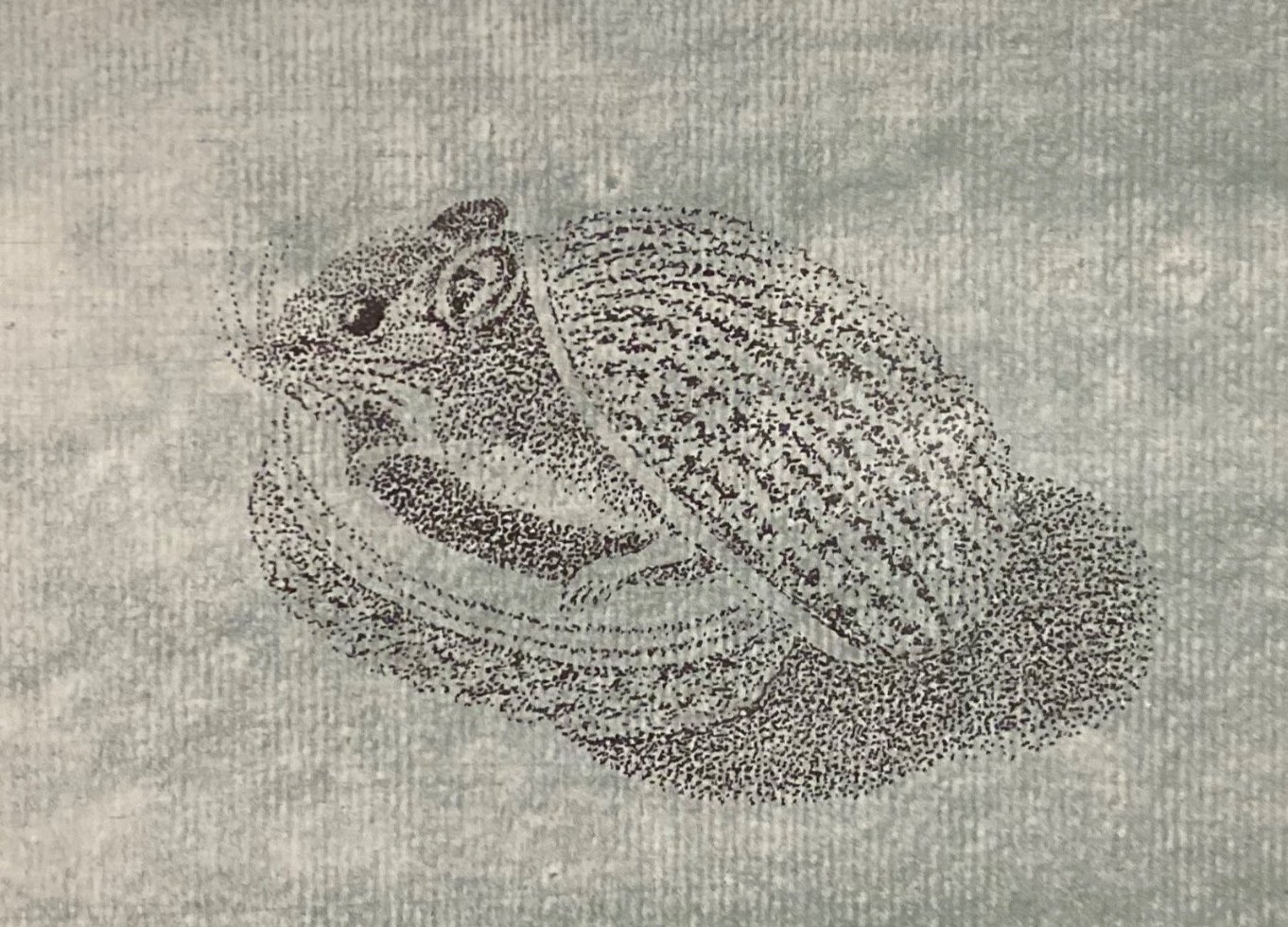

Both Huppler and Jackson were largely self-taught, worked at a small scale, and each forged a notoriously singular figurative style and material practice. In the late-1940s, Huppler first pioneered his stipple drawing technique, which would become his signature mode for next several decades. His delicate stipple drawings of mystical Italian landscapes, animals, and, later in his career, male nudes, teem with thousands of hand-drawn ink dots. Jackson, on the other hand, turned much of her energy towards painting, packing her gem-like fanciful compositions with all manner of plants, people, and animals engaged in curious activities, enlivened by a fastidious line and vibrant color palette. Despite their explorations in different media, Huppler and Jackson shared a penchant for fantasy and whimsy, a love for animals and the natural world, and a supreme dedication to craftsmanship and mark-making. Their shared dedication to figuration is also notable, especially at a time when large-scale abstract painting was en vogue. It is not surprising then, that in 1954—the same year Huppler befriended Andy Warhol— he would show at the Maynard Walker Gallery in New York, which specialized in the figurative works of American Regionalists like Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood. Jackson would also have a her own solo show there the following year.

Given the relative unpopularity of small-scale figuration during the height of their careers, Huppler and Jackson nonetheless became part of the Post-War American avant-garde, moving in circles which included the artists George Platt Lynes and Paul Cadmus, the writer and impresario Lincoln Kirstein, the art dealers John Bernard Myers and Betty Parsons, the poet James Merrill, and the heiress and patron Alice DeLamar, among many others. Despite their reclusive tendencies, Huppler and Jackson both managed to forge lasting connections with the art world elite, each becoming a classic example of the insider-outsider artist. Jackson’s 1968 solo show at Betty Parsons Gallery shared the gallery space with an exhibition of works by Richard Tuttle—a jarring and yet demonstrative juxtaposition that demonstrates this in-between status.

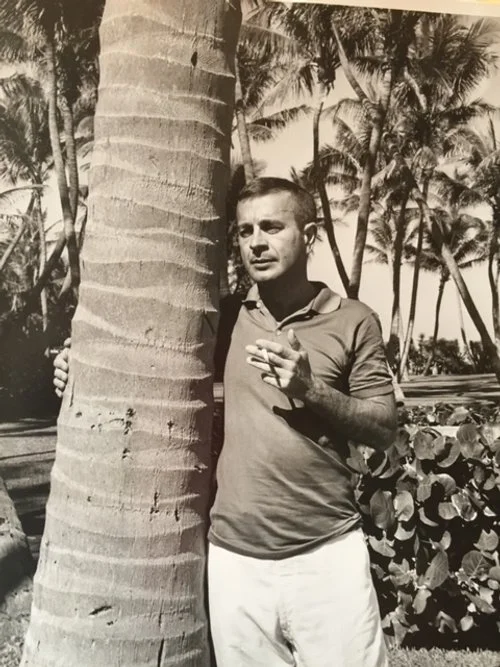

Despite serious interest in their work from the 1950s through the 1970s, especially among well-placed friends and colleagues in New York City, Huppler and Jackson nonetheless struggled to find lasting success and notoriety. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, both artists would rely heavily on the patronage and friendship of Alice DeLamar, whose Palm Beach, Florida estate became a de-facto winter studio for both artists. In a letter to Huppler from the 1960s, which very much encapsulates the spirit of the their art and of the time, DeLamar writes, “The pool is just right for swims and has been ever since I got up — Jean is busy painting again and is feeling fine.”

The Magic Realism of Dudley Huppler & Jean Jones Jackson will remain on view online through February 28, 2023, and works will be available in person by appointment. For further information, please email Gilles Heno-Coe at gilles@sideroomgallery.com.

Jean Jones Jackson, Southern Comfort, c. 1950s, gouache on card, 3 1/4 x 5 1/4 inches

Dudley Huppler, Rome (Owl in Trees), 1953, ink on paper, 9 3/4 x 5 3/4 inches

Jean Jones Jackson, Baseball, c. 1960, ink on paper, 11 x 13 1/4 inches

Dudley Huppler, Pika Hare on Nailsea Weight, c. 1956, ink and casein on paper, 9 3/4 x 7 inches

Dudley Huppler, Mouse in a Walnut Shell, c. 1960, ink and casein on paper, 4 1/4 x 6 inches

Jean Jones Jackson, Imaginary Walrus, 1964, oil on Masonite, 5 1/2 x 6 1/2 inches

The walrus has mislaid his speech.

Gowns and fedoras of the Mauve

Decade beset a twilit grove,

A desert dune, a coral beach.

The heart of hearts so small, so green

And limpid, cannot weep or smile.

Swamp willow and bull crocodile

Emergent moralize our scene.

Into that everglade Claudette

Is disappearing, her straw hat

Borne offstage by a kindly bat…

Her rosebuds float a while on jet.

-James Merrill, “To Remember J.J.J.,” 1985

Dudley Huppler at Alice DeLamar's Palm Beach, FL Estate, n.d.. Image courtesy Nona Footz.

Jean Jones Jackson, n.d.. Image courtesy Nona Footz.

A precocious, self-taught artist, Dudley Huppler (1917-1988) studied English at UW-Madison in the late 1930s and joined Marshall Glasier’s salon, which included Midwestern Surrealists like Karl Priebe, John Wilde, Sylvia Fein, and Gertrude Abercrombie. In the 1940s, encouraged by friends including Wilde, Huppler begins making drawings, and in 1947, developed his signature stipple-dot technique, working almost exclusively with ink on paper for the majority of his career.

In 1949, Huppler began spending significant time in New York City, where through his art, ambition and natural talents, he penetrated the innermost circles of cultural aristocracy. By the time of his arrival, his work was already widely known through postcard reproductions of his drawings, and soon his work would find its way into the hands of collectors including W.H. Auden and Ezra Pound. The same year, he would befriend renowned photographer George Platt Lynes, who introduced him to many of the leading gay cultural figures of the time. Writing to Gertrude Abercrombie in February, 1950, Huppler remarks, “Oh did I ever get a welcome from Paul Cadmus and Jared French and a nice new painter called George Tooker, a cute name…I might as well be in Europe, I’m that happy.” In 1954, he first became acquainted with Andy Warhol and collaborated with him on various projects, meanwhile, in letters to his Priebe, he would facetiously refer to him as “Warthole.”

Despite his myriad connections with the gay art community, it was not until the late-1960s that Huppler was comfortable being fully “out” in his work. As art historian Robert Cozzolino writes, “The work on which Huppler’s reputation was founded is filled with puns, symbols, and in-jokes that simultaneously reveal and veil his sexuality.”

Throughout the 1970s, Huppler gradually abandoned his signature stipple technique in favor of a more “traditional” drawing method. From the mid-1960s until his retirement in the mid-1980s, he would teach English at The University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh.

Jean Jones Jackson (1907-1984) was an American Surrealist painter. After studies in Paris and at the Art Students League, she started drawing in 1947 and then painting in 1950. In the 1950s, she would have New York solo exhibitions at Hugo Gallery and Maynard Walker Gallery and eventually, in 1968, landed a solo exhibition at the famed Betty Parsons Gallery. Writing to Jean in January 1968, dealer and artist Betty Parsons remarks, “We had a very good time showing your paintings. Everybody, including the artists in the Gallery, were very enthusiastic about them. We sold eleven which I think is very good for a first show and I expect to sell the rest of them before summer.” Despite Jackson’s modest commercial success, positive critical reviews (including one in Time magazine in 1969) and placement in prominent art collections of the era (including those of Paul Mellon and the Metropolitan Museum of Art), her work struggled to gain the kind traction that other star members of Parsons’ stable easily did.

For much of her career, Jackson lived half the year in a barn on the river side of Newtown Turnpike in Weston, Connecticut which her patron Alice DeLamar turned into apartment units. Her dashing blue-eyed sailor husband, Sandy, was 20 years her junior and mostly lived in the Forge, a red antique building perched right on the edge of the road adjacent to Alice DeLamar’s CT estate. Like Dudley Huppler, many winters were spent with DeLamar at the South Ocean Boulevard estate in Palm Beach, a home which originally belonged to the American Modernist painter, Gerald Murphy. The spirit and atmosphere of her surroundings in both Connecticut and Florida would make their way into many paintings.

In Jackson’s copious letters in DeLamar she spoke mostly of the woods, Sandy’s “Hill Billy” friends, plants, flowers, trees and animals. She talked a little about her painting and longed for places where she could be alone, remarking in the early-1980s that, “There doesn’t seem any place I can get to be a hermit.”

Characterized by an exceeding fineness and purity of line, these drawings in pencil or pen are filled with the same fantasy and bizarrerie and create the same fragile, imagined worlds as do the paintings.

-John Bernard Myers, Remarking on Jean Jones Jackson, 1985