Hand and Eye: Works on Paper, 1941-2024

Dubem Aniebonam, Ralph Coburn, Allan D’Arcangelo, Douglas Degges, John Evans, Louise Fishman, Hans Gerber, Dwinell Grant, Ray Johnson, Marta Lee, Lee Maxey, Tom McGlynn, Betty Parsons, Ruth Root, Esther Ruiz, Attilio Salemme, Sewell Sillman, Chuck Webster, John Willenbecher, Jack Arthur Wood

January, 2025

Side Room Gallery is pleased to present its next online exhibition, Hand and Eye: Works on Paper, 1941-2024, which showcases twenty drawings, collages, and mixed media works on paper created over eight decades. This exhibition explores the space “in between”—between the material and the visual, abstraction and representation, spontaneity and design.

Louise Fishman, Untitled, 1990, mixed media collage on paper, 11 3/4 x 10 7/8 inches

Tom McGlynn, Untitled, 2023, pastel on colored paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches

Allan D'Arcangelo, Study for Proposition #2, 1966, acrylic, pastel, and graphite on paper, 10 x 9 inches

Lee Maxey, Shells, 2022, watercolor on paper, 7 x 10 inches

Ralph Coburn, Arc #5, 1959, cut paper on paper panel, 3 1/2 x 7 inches

Ruth Root, Untitled (Apple Pie of the Eye), c. 1998, mixed media on paper, 12 x 9 inches

Betty Parsons, Untitled, 1978, watercolor and gouache on paper, 10 3/4 x 5 3/4 inches

Marta Lee, Blue Chair & Flowered Hat, 2021, acrylic and Acrylagouache on paper, 10 x 8 inches

Chuck Webster, Untitled (Cathedral), 2015, ink on handmade paper, 13 1/4 x 11 inches

Many works in this exhibition—even the most meticulously crafted—emphasize the process of their making, drawing attention to their materiality. Louise Fishman’s visceral 1990 collage, for instance, captures the sensibility of a simultaneously frantic yet ordered mind, a determined hand working faster than the eye itself. This work was made the same year as a devastating studio fire and partakes of that tragic, yet resolute energy, with its torn, slashed, pasted, and painted strips of paper. Like Fishman, Betty Parsons’s 1978 watercolor and gouache palpably manifests its swift execution, with vivid gestural strokes and veils of watercolor bleeding into one another. Chuck Webster’s 2015 drawing Untitled (Cathedral), with its characteristic luster and rich patina, was created by vigorously scraping down thick handmade paper between successive washes of ink, visually manifesting in a single image a time consuming material process. In Blue Chair & Flowered Hat (2021), Marta Lee uses acrylic and Acrylagouache laid down in discrete, richly textured layers and set against a monochromic background. Depicting real world objects drawn into idiosyncratic arrangements, Lee’s still life holds the line between representation and abstraction, the recognizable and the mysterious, drawing and painting.

Like Lee, other artists walk the line between abstraction and representation. Lee Maxey, for instance, depicts a cluster of seashells, whose vivid interiors seem to open into other universes. Attilio Salemme, in his 1944 watercolor, depicts a tight-knit group of disembodied voyeurs as if transformed into a cluster of colorful geometric shapes. Allan D’Arcangelo’s acrylic and pastel drawing, Study for Proposition #2 (1966), demonstrates his longstanding dedication to landscape, here reduced to its most basic and suggestive elements: a hint of green grass and a band of blue sky. While strictly speaking non-objective in subject matter, Jack Arthur Wood’s mixed media collage evokes a yearning for landscape as well, where brightly colored gradients flash across a highly textured and optically buzzing field with an off-kilter symmetry.

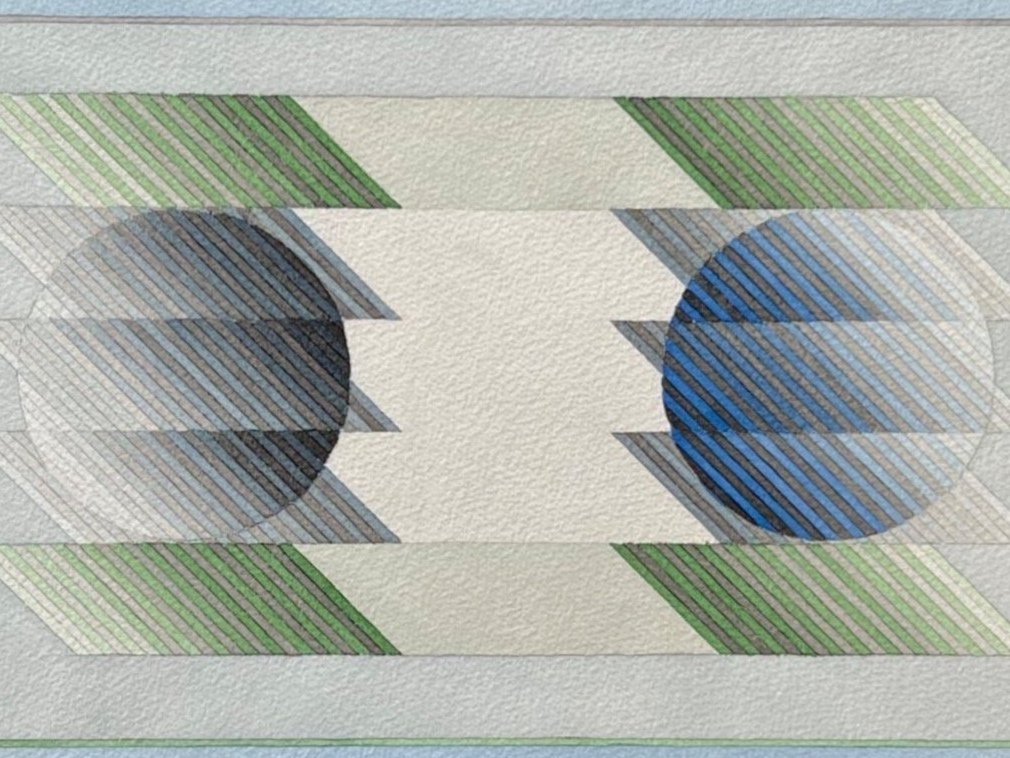

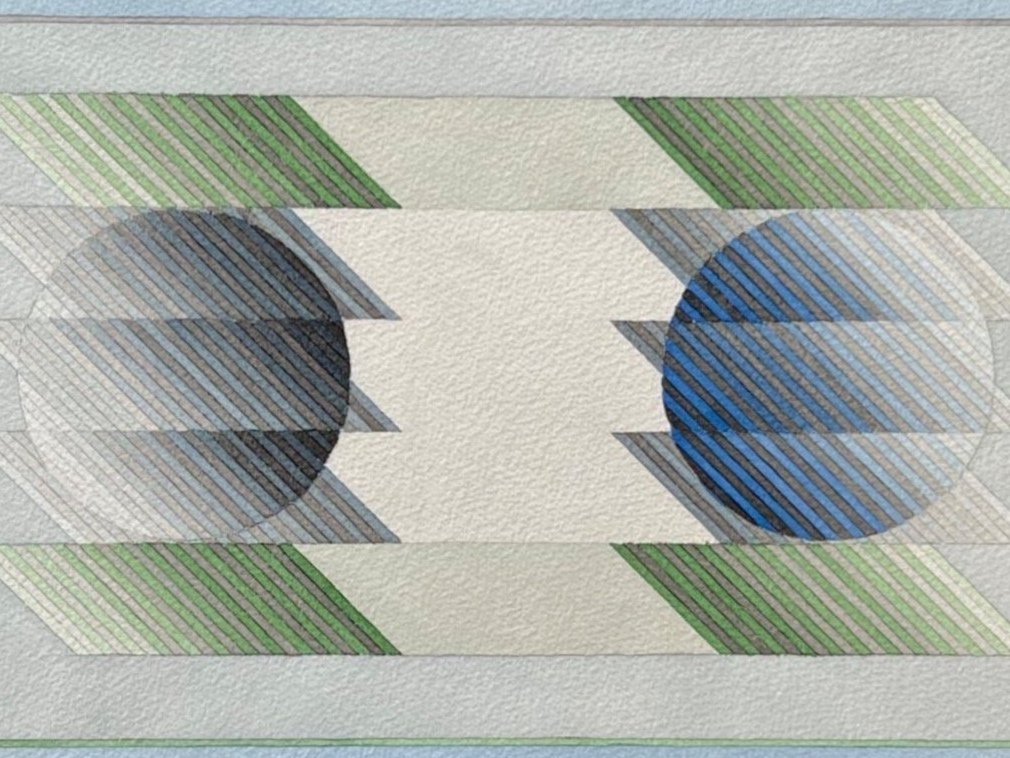

Sewell Sillman, Untitled [30 I 79], 1979, watercolor and graphite on Arches paper, 18 x 24 inches

Jack Arthur Wood, Land Fresnel, 2024, acrylic, fabrics, and glue on Arches paper, 18 x 24 inches

Tom McGlynn’s lively abstract pastel dispenses with representation entirely and appears to have been made without a hand at all, its finely tuned arrangement of colored rectangles forming a cozy cluster at the center of the sheet. McGlynn’s jaunty grid hums with energy, as if powered by an internal power source.

Other works were made as studies for paintings or sculpture, like Esther Ruiz’s Drawing for a Communication Device, 2024, which demonstrates this sculptor’s inventive approach to design, color, and composition, giving herself room for both play and planning. Ralph Coburn’s Arc #5, 1959, is related to the painting of the same name for which this small collage is a study, one whose scale belies its graphic punch. This simple and sophisticated collage demonstrates the artist’s penchant for distilling the essence of the observable world, solidifying moments of vision into elegant abstract arrangements. Sewell Sillman, a deft protégé of Josef Albers, similarly plays with the basics of visual perception and geometry in his 1979 watercolor. Depicting two orbs locked in a scintillating zig-zagged composition, this work showcases Sillman’s masterful understanding of shading, rhythm, and color theory, which he learned at Black Mountain College, then Yale, from his Bauhaus mentor.

Esther Ruiz, Drawing for a Communication Device, 2024, colored pencil on paper, 14 x 11 inches

Ray Johnson, Untitled [Wanda Gag], c. 1967, graphite on paper, 5 1/2 x 3 1/4 inches

John Evans, June 19, 1976, 1976, watercolor, rubber stamp, and collage on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches

In contrast with the time-consuming execution and fine-tuned precision of Sillman’s watercolor, Ray Johnson’s small graphite sketch demonstrates his penchant for immediacy, ephemerality, and humor, presenting itself as something halfway between a casual textual annotation and abstract drawing. Like Johnson, another artist who makes ample use of text in his work is John Evans, who is best known for his idiosyncratic mixed media collages, made daily for decades.

A younger student of watercolor and ink drawing, Douglas Degges, takes his cues from the likes of Eva Hesse or Tom Nozkowski, playfully skirting the line between abstraction and figuration, improvisation and preconception. This drawing demonstrates a sensitivity to both the hand and the eye, a feeling for texture and touch as well as formal considerations of line, composition, and color.

Hans Gerber’s abstract composition suggests a mind unleashed by the visionary possibilities of collage and whose crisply cut, simultaneously organic and synthetic forms lock into a visionary futuristic cityscape. Ruth Root also explores collage—a foundational technique for Surrealists—but much differently, awkwardly splicing together vividly and vigorously cut and painted sections of paper with handwritten text and ephemera, creating something both punchy and poetic.

Hans Gerber, Collage 69 / 773, 1969, mixed media collage on board, 5 3/4 x 7 inches

John Willenbecher, 5 II 92, 1992, acrylic on paper, 9 x 8 1/4 inches

Attilio Salemme, The Spectators, 1944, watercolor and ink on paper, 6 1/2 x 10 inches

Dubem Aniebonam, emerging 01, 2024, gouache, pencil, colored pencil, ink, on toned tan paper, 8 x 6 inches

Douglas Degges, Untitled, 2020, acrylic and walnut ink on paper, 7 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches

Dwinell Grant, Contrathemis, 1941, collage and colored pencil on tracing paper, 8 x 10 7/8 inches

John Willenbecher, best known for his box assemblages from the 1960s, turned in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s to depicting the variegated patterns of cut slabs of stone and marble. Not satisfied with merely copying these natural formations, John decided to invent his own, skirting the line between recreation and invention.

Dwinell Grant was an abstract artist and pioneering avant-garde filmmaker. His early experiments in non-objective animated film greatly impressed Hilla Rebay, ultimately landing him a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1940. His filmic masterwork, Composition #2: Contrathemis (1941, silent), lasts less than five minutes, but is animated by over four thousand frames, necessitating an inordinate number of drawings and collages for this purpose. As with Grant’s collage, Dubem Aniebonam economically reduces her palette and composition, anchoring the sheet with a black half circle intersected by a hazy red halo, creating a wonderful tension between atmospheric depth and pitch black flatness.

For further information, please contact Gilles Heno-Coe at gilles@sideroomgallery.com.

![Sewell Sillman, Untitled [30 I 79], 1979, watercolor and graphite on Arches paper, 18 x 24 inches](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/63b70e331deebc318f75001b/1730527212354-NQDBF4S0S2BS4SBXHAP1/IMG_0024_scaled.jpg)

![Ray Johnson, Untitled [Wanda Gag], c. 1967, graphite on paper, 5 1/2 x 3 1/4 inches](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/63b70e331deebc318f75001b/1737207091529-RGQHI6PF6MLDU4C7RLX6/IMG_1091%2B2.jpg)